Unwrapping the resource management reform

The Government introduced the Natural Environment Bill and Planning Bill (Bills) set to replace the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) on 9 December. The Bills will have their First Reading next week and be referred to the Environment Select Committee, when the closing date for submissions will be advised. The Government intends the Bills to become law in mid-2026.

The Bills largely follow the recommendations of the Expert Advisory Group published in March 2025, and Cabinet’s subsequent decisions on those recommendations.[1] The Bills have been developed with a clear focus on achieving a core guiding principle of the Government, being the enjoyment of property rights.

At a high level, the replacement of the RMA will involve regulation and policy split between two new Bills:

- The Natural Environment Bill (NE Bill) establishes a framework for the use, protection and enhancement of the natural environment. This includes land, water, air, soil, minerals, energy, plants (excluding pest species) and animals and their habitats.

- The Planning Bill establishes a framework for planning and regulating the use, development and enjoyment of land. It manages a narrower scope of effects than the RMA.

The Government has also introduced a separate Resource Management (Duration of Consents) Bill under urgency on 9 December 2025. This Bill introduces a new section 123C to the RMA which will allow existing consents with expiry dates before 31 December 2027, or which have already expired and the consent holder was operating on the existing consent under section 124 of the RMA, to be extended until 31 December 2027. In the case of already expired consents that are within the scope of the extension, they are ‘reinstated’.

Some consents will not benefit from these extensions, those including:

- where the consent relates to water (including water permits and discharge permits) the consent will expire the earlier of 35 years after the consent commenced or 31 December 2027, and

- any extant wastewater consents that were extended under recent amendments to the RMA.

This article covers the essentials to be aware of on introduction of the Bills. We summarise the who, when and what of the Reforms, as well as highlighting some elements that are likely to attract submissions. We will release three more detailed articles on the Bills that focus on: infrastructure/energy, urban development and the implications for local government.

Who does what?

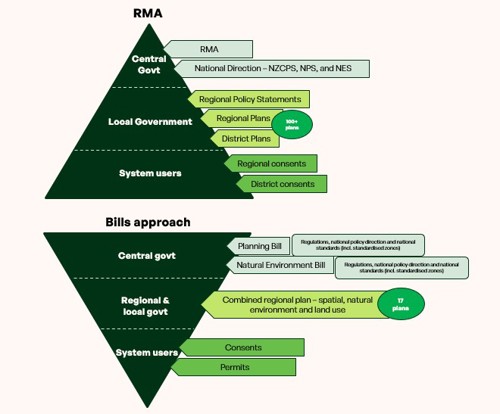

There is a greater role for central government, narrowed scope for environmental regulation and clear standards for implementation . Central government will deliver one combined national policy direction and national standards in two tranches, one due in late 2026 (including instruments for setting limits for life-supporting capacity and human health, national standards for regional spatial plans and some national rules to support the transitional consenting regimes) and the other in 2027 (covering national standards for making land-use plans and standardized plan content for land and soil). The national standards will set some environmental limits, with others to be set in regional combined plans.

Councils retain their plan making functions, albeit the plans are now called regional spatial plans, natural environment plans, and land-use plans - together forming a combined regional plan. The split of functions between regional councils and territorial authorities remains largely the same as under the RMA, with district councils responsible for land-use plans and regional councils responsible for natural environment plans. The spatial plans will be jointly prepared by all councils in the region. The spatial plan informs the others and is made first.

This means that the hierarchy under the new system is:

- goals, set in the Bills (no hierarchy)

- national policy direction

- national standards

- regional spatial plans

- land use plans and natural environment plans.

Each instrument must ‘implement’ the instrument higher up the hierarchy.

The overall shifting of the design of the system is shown on the diagram below [click to enlarge]. The Government considers that this approach will reduce the number of consents needed and refers to it as the ‘funnel system’.

When will it happen?

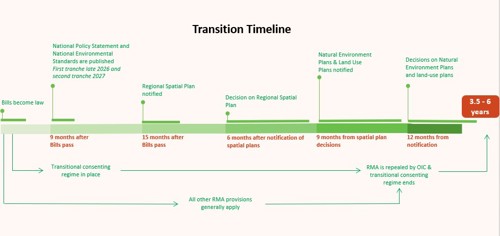

The RMA will continue to apply while the new system is being established. The ‘plan stop’ will be extended and apply during this period.[2]

The RMA will ‘die’ by Order in Council only when all proposed plans under the new system have been notified. While no date has been set, the Government has stated that the new system will be fully operational in 6 years. At this point, notified plans would have legal effect and the new planning system will be 'switched on', with all new system instruments and processes applying instead. This means the RMA system will continue to be the law for around 3.5- 6 years after enactment of the Bills.

Significantly there will be a 'transitional consenting framework' that will apply between one month after Royal Assent and the Order in Council setting the ‘transition date’ for the ultimate repeal of the RMA is made.

The transitional consenting framework includes some elements of the Bills:

- the removal of the special circumstances test for public notification

- exclusions on the scope of effects

- provisions on financial assurances and bonds

- application of procedural principles

- consideration of any new national standards and rules (once developed)

- consideration of spatial plans (once developed).

This transitional consenting framework has the potential to create uncertainty for a significant period of time while some components of the new system will apply to an otherwise status quo for resource consenting. On the other hand, the automatic extension of consents set to expire by way of the separate ‘Duration of Consents’ Bill will be welcome news for many stakeholders.

The key timing provided for in the Bills is shown on the diagram below [click to enlarge].

What will the Bills do?

- The Bills’ purpose is to set up the new system. Each Bill contains ‘goals’ that set out the substantive outcomes. There is no hierarchy between the goals. ‘Sustainable management’ is not on the list, the focus is on enabling use and development of natural resources within environmental limits and supporting and enabling economic growth via enabling the use and development of land. The Goals include several RMA matters of national importance and other matters (ss 6 and 7) such as indigenous biodiversity (phrased as a no net loss goal), ONF/Ls, managing natural hazards, and maintaining public access to and along the coastal marine area, lakes and rivers. Other matters are notably absent, such as amenity values, effects of climate change, kaitiakitanga, and the relationship of Maori and their culture and traditions with their ancestral lands, water, sites, waahi tapu, and other taonga), and a number of economic, infrastructure and development goals have been added.

- There is no longer an operative Treaty of Waitangi principles provision. The ‘Goals’ include providing for Māori interests in specified ways and the Bills seek to provide for Treaty settlement obligations. This element of the Bills is likely to be a focus of submissions.

- he Bills both contain procedural principles, such as proportionality, acting in a timely and cost effective manner, and act in an ‘enabling manner’ that all decision-makers will need to take all practicable steps to achieve.

- One (combined) national policy statement under each Bill and national environmental standards (now called national instruments) (to set some environmental limits and give direction on standardised zones) are intended to provide standardised national direction. MfE has stated that the first set of the national direction package is intended to be ready at the end of 2026.

- Broad regulatory making powers are given to central government. Regulations may address administrative, procedural, financial, compliance, enforcement, and ‘emergency matters’.

- Regional combined plans that include spatial, natural environment and land-use plans are to be created, meaning there will no longer be individual plans for each district. All councils in the region are to jointly prepare the regional spatial plans, with regional councils preparing natural environment plans, and district councils preparing land-use plans. Councils will need to choose zones from the standardised national direction.

- Regional Spatial Plans will support urban development and infrastructure provision within environmental limits by identifying on a 30-year horizon growth areas, infrastructure corridors and areas needing protection;

- Natural Environment Plans will apply standardised overlays rules, and methodologies;

- Land-use plans will apply standardised zones, rules and methodologies.

- Environmental limits are to be embedded in regional combined plans. Councils will need to develop action plans where limits are breached and at risk, and activities will generally not be able to breach environmental limits (with limited exceptions for infrastructure).

- Special process for ‘bespoke planning provisions’ where a plan is to include non-standard provisions there will be a specific and more stringent process including allowing further submissions and merit appeals. Otherwise, submissions on plan provisions will be limited.

- Plans will be able to include provisions for land release or land-use change to occur at a trigger point (such as the availability of specific infrastructure).

- Improvements to designations are provided. Designating authorities will have a role to play in deciding what planning provisions are to apply to their sites, and designations can be achieved by inclusion in the regional spatial plan (rather than using the RMA notice of requirement process).

- Controlled and non-complying activity classifications no longer exist.

- More activities to be permitted, including activities with less than minor adverse effects, ‘routine low risk activities’ permitted subject to conditions.

- Permitted baseline is mandatory except if the activity involves the allocation of natural resources.

- Certain effects excluded from consideration (discussed in more detail below).

- Notification and submissions are curtailed. Only those “materially affected” can participate. Limited notification will only be given where effects are “more than minor” (lifting the current bar from minor). Public notification will only be given where effects are significant and/or all affected parties cannot be identified (depending on which Bill applies). Special circumstances as a reason for notification is no more.

- Applicants have an opportunity to review draft conditions before decisions are finalised.

- The new tools include adverse publicity orders, monetary benefit orders to recover commercial gain, enhanced financial assurances including clean-up assurances and changes to bonds, enforceable undertakings, and a pecuniary penalty regime that provides civil accountability for situations where criminal sanctions may not be appropriate.

- - Planning Tribunal to be set up for ‘smaller disputes’. The Planning Tribunal will be established as a division of the Environment Court. The key functions of the Planning Tribunal will include reviewing administrative decisions made in the processing of consents and permits, for example, requests for further information, notification decisions, interpreting consent conditions, and being able to strike out consent conditions that are deemed to be out of scope of the system. The Planning Tribunal will not have a role in hearing appeals on plans, designations, and notified consents and permits where there are third-party submitters, nor deal with enforcement matters.

Potential hot topics

Scope of effects

The scope of the effects able to be considered in the Bills is significantly curtailed as the Government has foreshadowed with the Bills containing a list of effects that must be disregarded under the Planning Bill.

| EFFECTS IN SCOPE | EFFECTS OUT OF SCOPE |

|---|---|

| Natural hazards | Internal to the site - eg building layout, private open space, balconies |

| 'Significant' historic heritage | Financial viability and demand for a Project |

| Noise and vibration | Visual amenity |

| Shading | Views from private property |

| ONF/L and High Natural Character areas | The social and economic status of future residents (ie whether the residential use is social housing) |

| Positive effects | Impacts on competing businesses / trade competition / retail distribution |

| Sites of significance to Māori | 'Subjective' landscape effects |

| Effect of setting a precedent | |

| Effect on landscape (other than for high natural character or outstanding natural landscapes and features) | |

| Where the land use effects of an activity are dealt with under other legislation |

How some of these exclusions will be applied in practice could be a controversial topic.

Regulatory relief

The regulatory relief framework will require councils to consider the impact on private landowners of planning controls on:

- indigenous biodiversity and significant natural areas

- significant historic heritage, and sites of significance to Māori

- outstanding natural features and landscapes

- areas of high natural character in the coastal environment, wetlands, lakes and rivers and their margins.

Where the impact is significant or more than minor then councils have to provide relief.

Councils would be able to use a range of tools when providing relief, including rates relief, bonus development rights, no-fees consents, land swaps, access to grants or expert advice, and payment of compensation. The Planning Tribunal would have a role in resolving disputes about how councils have provided relief.

This element of the Bills is relatively novel in New Zealand law. To force the regulator to pay for planning rules addressed and protecting the ‘public good’ would arguably deter the recognition of those important environmental matters. While the RMA does contain a compensation provision where the land is ‘incapable of reasonable use’, it seems that ‘regulatory relief’ is about what the plan is applying to the land rather than what it can be used for as a result. This topic is likely to be significant for submitters on the Bills, particularly local government, interest groups, and Māori.

Whether the reform will deliver the promised (and much anticipated) ‘once in a generation shift’ will turn on the details of the Bills. There is a significant amount of information to digest, and we plan to provide our more in-depth insights shortly.

[1] Refer to our previous article here: Simpson Grierson - RMA Reform: Beyond the headlines

[2] See our article explaining the plan stop here: Simpson Grierson - Government announces halt to Councils’ plan-making in preparation for the new RMA system.